Meg Hitchcock

Barbara Friedman

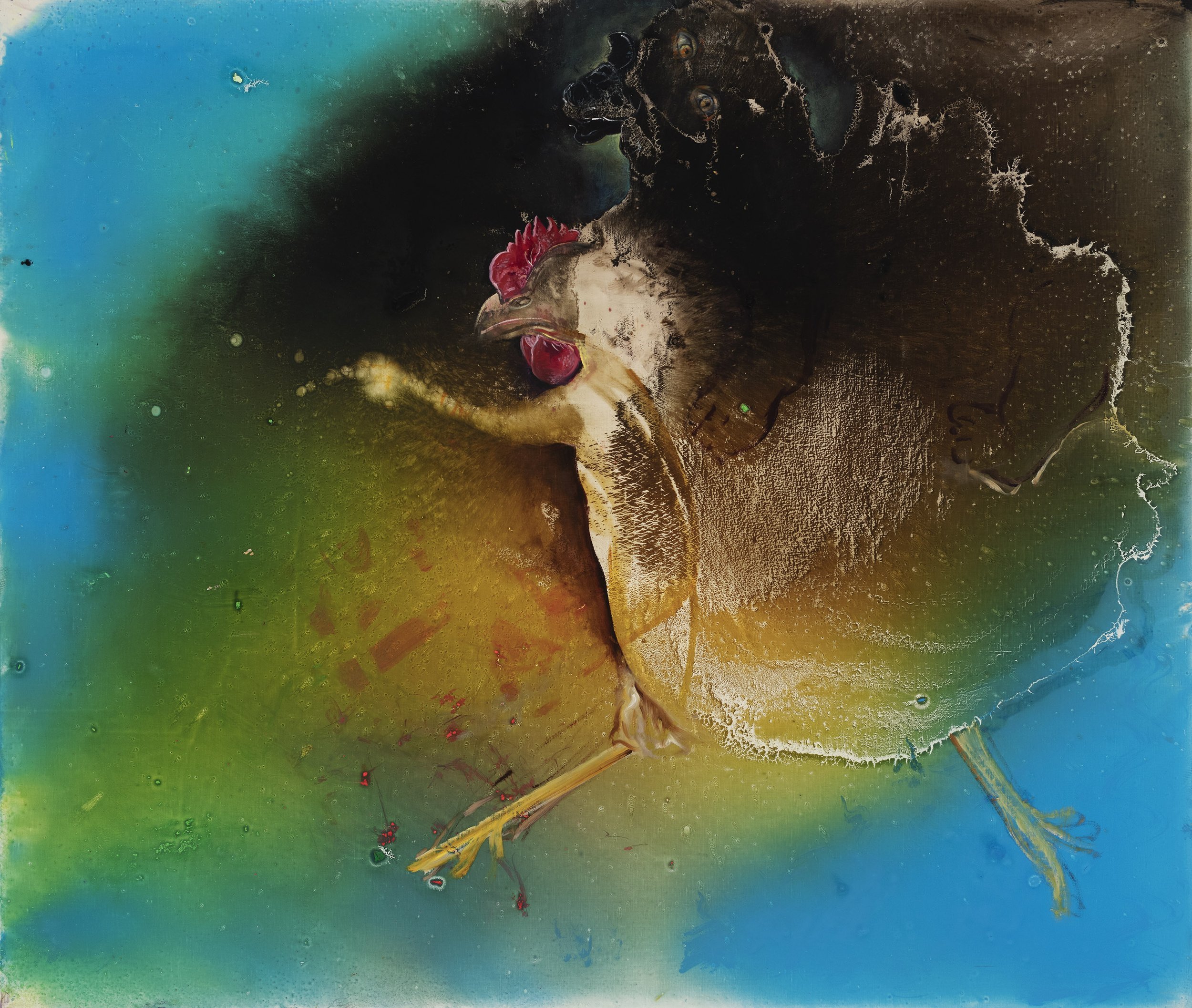

In her current show at Five Myles in Brooklyn, Barbara Friedman explores the tenuous relationship between pure abstraction and painterly figuration. “The Hysterical Sublime” consists of a series of formal color field paintings that appear to have been hijacked by a legion of zoomorphic creatures. In a dual process of discovery and intervention, Friedman liberates the creatures from the paint, endowing them with enough agency to administer to each other’s needs. The creatures make us feel slightly uneasy as they confront our curious gaze, but Friedman seems to regard them as her allies, despite the havoc they’ve wreaked upon her pure color fields. But maybe that was her intention all along—namely, to turn formal painting on its head and poke fun at it. She readily admits that the creatures are ridiculous, illogical, and skeptical of art movements. They’re about intimacy and connection rather than the critical concerns that characterize nonrepresentational painting. The anthropomorphized animals imbue the paintings with heartbreaking humanity, making it hard to look at them and harder to look away. Whether by accident or design, Friedman paints a portrait of our species more relatable because her subjects are animal rather than human. While we’ve become woefully inured to the afflictions of our fellow humans, few among us can bear to witness the suffering of an animal. But I may have it all wrong; the creatures may not be like so many actors in a Greek tragedy. They may be perfectly content in their two-dimensional habitat, blithely chomping their way through fields of pigment and mocking any attempts at critical art theory. If Friedman’s would-be color field paintings have indeed been usurped by snakes, snails, whiskers, and whales, it’s doubtless for our benefit. The art world won’t suffer the loss of another purely abstract painting, but it can surely afford to take itself less seriously.

MH: Your canvases are very painterly and hover on the edge of pure abstraction, but for the mythic animals that emerge and hijack your paintings. Who or what are these creatures, and when did they first make an appearance in your work?

BF: I love the word hijack! And the creatures really do hijack my recent paintings, because they start off as pure abstraction but once the paint dries fully, the creatures emerge. Before the pandemic I would paint something that I would then eradicate and allow to mutate into something else. I no longer start with a preconceived image, but with as little intervention as possible, I bring out the imagery that the poured pools of oil paint seem to suggest.

MH: There’s a Hieronymus Bosch vibe in your work, where the creatures seem to have considerable agency and intelligence. I’m thinking of the lobster, who’s drinking the melted butter that he’ll later be dipped into. And he’s aware of it, which makes my heart hurt. How do you think about them?

BF: I like the ridiculousness of the creatures. It’s about their interconnection – they’re hanging over each other, breathing into each other’s mouths, kissing, licking, all the things we aren’t allowed to do. The lobster is particularly maudlin, and I rendered the bowl of butter concretely, which is unusual for this series. I felt that it needed something there formally. It’s about desire, intimacy, fear.

MH: The imagery expresses a deep pathos, as if the creatures are making the best of a situation beyond their control. Which could also describe the human experience, as we flail about and try to make sense of our abstract existence. Do you ever think of them as self-portraits, or profiles of humanity?

BF: Yes, absolutely. I’m not sure where the distinction lies. I think they’ve merged with each other, and there’s an interspecies merging as well. I see them as hybrid creatures that harness the vastness of the abstraction. They’ve escaped from a toxic environment, because they emerge from oil spills, and yet they still have souls.

MH: They do have a toxic feel to them. And they’re a little threatening! It’s unsettling when an animal has that much agency.

BF: I love the idea of them having too much agency!

MH: Right? A cat is cute when it’s curled up on your lap, but you’d be uncomfortable if it started walking around on its hind legs with a pair of scissors. And that’s how I feel about your creatures; I’m trying to feel good about them, but their intelligence makes me uncomfortable.

BF: Haha! Honestly, these paintings are odd to me as well. But I do have this figurative impulse, and I think there’s also love and intimacy between the figures. But I’ve never told stories that were anything but open-ended.

MH: Do you have any insight into why you see animals in your paintings rather than, say, trees or tangerines?

BF: I wanted to take the whole painting and with a few interventions, turn it into something specific, something that seemed inevitable, like it had to be this thing. At heart I’m a portraitist; I was the kid who drew faces in fifth grade. So it was interesting to harness the paint and nudge it into something. It’s like pareidolia, where you see recognizable forms in random patterns. What I saw were these creatures and their interrelationships.

MH: You said that you sometimes refer to your work as “contaminated color field paintings”. What do you mean by this?

BF: I want them to be viscerally satisfying as color field paintings, then I want to thumb my nose at the seriousness of it. Adding the figures is exactly what you’re not supposed to do! The last thing that most abstract painters want is to have any perceivable imagery in their paintings. If they think something looks like a bunny rabbit, they’ll immediately change the painting. I’m doing the opposite, and that’s what I mean by contamination. But I want both to coexist if possible.

MH: Do you think that’s possible? Can a work be completely abstract and have imagery?

BF: Probably not, but I’m not interested in making purely abstract paintings. I love pure abstraction, but then I want the imagery to snap into focus. I may have an idea of where I want the painting to go, but it doesn’t always go in that direction. Each painting is unique and has its own life, and then it becomes just about making it work on a formal level.

MH: The creatures are quirky and painterly, but they’re somewhat distracting. They may interfere with one’s ability to relate with the painting formally.

BF: A lot of people feel that way, and it frustrates me sometimes. Like if someone was to refer to me as the artist who paints animals, I’d hate that. I feel like my work operates on many levels, including the formal.

MH: I suppose pure abstraction without any figuration can be sublime, but it’s not very relatable. By adding these creatures, are you making the sublime more accessible?

BF: Yes, there’s the desire for relatability, for contact and connection – to reach across an abyss. There was a lot of opacity in my family when I was growing up, so there’s a part of me that wants to reach out to people and connect.

MH: Right, I can see how your paintings could establish a horizontal connection with the viewer. Do you also think about vertical connections?

BF: You mean spirituality? I’ve been told that I’m deeply secular, which is really sad, if true. I’m very skeptical by nature, but I don’t sit happily by it.

MH: When you’re in your studio and in the flow, do you feel any kind of vertical connection, like something’s coming through you? Not in a religious sense, but like you’re tapping into something ineffable?

BF: Yes, totally. But I don’t know how to ascribe that. I’m a very romantic painter, and I act on essentialist assumptions that are so modernist and retrograde. I feel like I’m searching for something…

MH: Maybe it’s neither a horizontal connection with other people nor a vertical connection with some deity – maybe you’re just connecting with your creatures!

BF: Hahaha! Maybe, but whatever kind of painting I’m making, I feel like there’s a secret to be found, something waiting to be pulled out. I just don’t know the way there, so I have to keep digging until I find it. And that’s what keeps it interesting.

MH: What you’re describing requires some magical thinking! You’re diving into these paintings with the faith that you’re going to find whatever’s in there, waiting to be excavated. So maybe you’re not so deeply secular after all.

BF: It’s totally magical thinking. I approach art making completely through magical thinking – I want to be surprised. I’m looking for the accident that charts the way forward. It’s the only way I enjoy working; otherwise, I’d just be illustrating an idea, and my ideas aren’t that interesting.

MH: So you start a painting in search of something, and all along the way you make allowance for accidents to disrupt and detour your process. It seems that what you’re searching for is a moving target.

BF: Oh, it’s always a moving target. But this is how I’ve always worked, I’ve just done it in different ways. All my characters and creatures happen during the process; they offer themselves up to me along the way.

MH: You’ve said that you want to make your work funny and ridiculous, and at the same time you want to “harness the sublime”. Are they the same? The ridiculous and the sublime?

BF: I want to see the ridiculous in the sublime. Maybe I’m also mocking the sublime, toying with it, bringing the lofty down to size. But it’s still lofty! I’m not destroying it, I’m humanizing it.

MH: Do the creatures give you something to push against?

BF: I’d say that the abstraction gives me something to push against. It’s a back and forth process, and very angst-ridden. I do the initial pour with lots of turp and pigment, then when it’s dry, I intervene with the imagery, then I’ll go back and pour again, reestablishing the abstraction. So it’s really the abstraction that I’m pushing up against.

MH: Do you think that pure abstraction is better suited to take the viewer to an elevated state, simply because there’s no visual noise? Or would a landscape or dog portrait do a better job because they’re more relatable?

BF: It’s a great question. I think either can do the job, and I can have a transcendent experience through either. It’s totally subjective.

MH: The title of your show is “The Hysterical Sublime”, which is from an essay by Fredric Jameson. What was Jameson referring to, and what about this is intriguing to you in reference to your paintings?

BF: It's Jameson's phrase that gripped me rather than his analysis of the phenomenon that it names. I don't think he’s imagining the old kind of sublime, which would be something higher and grander. Jameson is suggesting that human beings have constructed an elaborate culture that keeps us estranged from nature, and that this construction is itself overwhelming. His essay intrigued me because it seemed to be pointing to what I was playing with, and there’s an element of hysteria in these paintings. I feel like I'm in dialogue with natural objects and processes, and yet aware of how my side of the dialogue is itself a massive construction.

MH The creatures that emerge from your paintings appear to be hysterical. Are they also sublime? And do they offer you the possibility of transcendence?

BF: I agree that they're hysterical creatures. I find them to be sublime too, in the sense that their appearance in the paintings is beyond my control. But I don't imagine people feeling like the paintings take their breath away, in that sense of the transcendent. The creatures are hysterically sublime in the sense that the art making is hysterically overwrought.

MH: What’s the best part about being an artist?

BF: I think we all love the psychological and intellectual freedom. It really does feel like you don't have to grow up. But I would also say that I love the kind of learning that such freedom makes possible, which is very much an accumulative learning. This just gets better with age. So now, after however many years of painting, I can feel as though what I do in the studio brings together everything I have learned in past years, both from my own work, my reading, my life experiences, as well as from all the art by other people that I have taken in.